Closed for Christmas and New Year’s Day

In observance of the Christmas Holiday, SEPA Labs will be closed on Monday, December 25th, 2023. We will reopen on December 26th.

We will also be closed on New Year’s Day, January 1st, 2024 and will reopen on January 2nd, 2024.

Patrick E.T. Godbey, MD, FCAP, FACOG, Named Pathologist of the Year by the College of American Pathologists

Patrick E.T. Godbey, MD, FCAP, FACOG, Named Pathologist of the Year by the College of American Pathologists

NEW ORLEANS, La–The College of American Pathologists (CAP), the world’s largest organization for the medical doctors who diagnose and study disease, recognized several of its members for their contributions to pathology and laboratory medicine during its annual meeting, in New Orleans, Louisiana October 8-11, 2022.

In recognition of his long and distinguished career in pathology, the CAP named Patrick E.T. Godbey, MD, FCAP, Pathologist of the Year. During his 30 years as a CAP member, Dr. Godbey served two full terms as a member of the CAP Board of Governors. He was the chair of the Council on Government and Professional Affairs, overseeing the direction of the organization’s legislative and regulatory advocacy efforts on behalf of patients, pathologists, and medical laboratories, and he has led numerous CAP councils and committees.

“I am humbled to be named the Pathologist of the Year. So many pathologists immediately took up the fight against COVID-19 and we much more than answered the call,” Dr. Godbey comments. “It was my privilege to lead the CAP during this most challenging of times. I am certainly honored to be the recipient of this prestigious award, but I know that there are a large, large number of Fellows in this College who are also truly Pathologists of the Year.”

From 2019 to 2021 Dr. Godbey served as CAP president. He skillfully led the CAP through the COVID-19 pandemic by positioning and promoting pathologists as indispensable. He also increased the flexibility and visibility of the laboratory throughout the pandemic. In addition, he led the CAP during the social justice movement of 2020, during which he condemned racism, inequity, and discrimination in any form. Dr. Godbey directed the formation of the CAP’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion Committee. Further, Dr. Godbey conceived and helped direct the pathologist’s pipeline initiative, working to introduce the pathology specialty to more medical students.

Dr. Godbey joined the Southeast Georgia Health System medical staff in 1983 as an obstetrician and gynecologist before transitioning to the practice of anatomic and clinical pathology. He is a Fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, a board member of the Georgia Association of Pathology, and a member of the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society, Phi Beta Kappa, the Chinese American Pathologists Association, and the Florida Society of Pathologists.

Dr. Godbey founded Southeastern Pathology Associates where he serves as CEO and laboratory director. He is also the chief of the Department of Pathology at Southeast Georgia Health System in Brunswick, Georgia and chair of the board of the Camden Healthcare Network.

In addition to the Pathologist of the Year award, the CAP recognized 19 other members/residents for their contributions, achievements, and service in a multitude of areas, including but not limited to advocacy, patient care, education, quality improvement programs, and communications.

About the College of American Pathologists

As the world’s largest organization of board-certified pathologists and leading provider of laboratory accreditation and proficiency testing programs, the College of American Pathologists

(CAP) serves patients, pathologists, and the public by fostering and advocating excellence in the practice of pathology and laboratory medicine worldwide. For more information, visit: newsroom.cap.org and yourpathologist.org to watch pathologists at work and see the stories of the patients who trust them with their care. Read the CAP Annual Report.

SEPA IS HIRING – JOIN OUR TEAM

SEPA IS HIRING!

Open Positions Include:

Medical Claims Specialist

Patient Support Advocate

Managed Care Representative

Administrative Assistant….and MORE!

The Impacts of a Breach Newsletter – July 2021

The Impacts of a Breach Newsletter – July 2021 Security Newsletter

Hurricane ELSA

ELSA UPDATE

We are continuously monitoring ELSA for any changes that will affect SEPA operations. As of now, SEPA is under normal business operations. Status updates will be available as conditions changes.

Memorial Day 2021

Published May 23, 2014

In observance of Memorial Day, SEPA Labs will be closed on Monday 31, 2021. For access to the “on call” pathologist, please call 912-279-1900 or 888-261-2671.

COVID-19 UPDATE:

SEPA LABS remains committed to providing quality and timely services during the COVID-19 situation. All SEPA locations are open and providing services to our clients.

SEPA CELEBRATES 28 YEARS OF SERVICE

SEPA Labs Celebrates 28 Years Of Service

SEPA Labs celebrates its 28th year serving the medical communities of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina. SEPA continues to grow because of the hard and good work and dedication of our staff, present and past.

Thank you!

Pat Godbey MD, FACOG, FCAP

CEO Southeastern Pathology Associates

Pathologist’s Corner – Dr. Amira B. Fanous-Paul on Lung Cancer

Lung Cancer Prevention and Early Detection:

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in both men and women (not counting skin cancer), and is by far the leading cause of cancer death among both men and women. Each year, more people die of lung cancer than of colon, breast and prostate cancer combined.

Most lung cancers could be prevented, because they are related to smoking (or secondhand smoke), or less often to exposure to radon, asbestos, or other environmental factors.

Most lung cancers have already spread widely and are at an advanced stage when they are first found, but in recent years, doctors have found a test that can be used to screen for lung cancer in people at high risk of the disease.

Screening is the use of tests or exams to find a disease in people who don’t have symptoms. In recent years, a test known as a low dose CAT scan or CT scan (LDCT) has been studied in people at a higher risk of getting lung cancer.

American Cancer Society Guidelines for Lung Cancer Screening:

The ACS recommends yearly lung cancer screening with LDCT for people who are 55 to 74 years old, are in fairly good health, and who also meet the following conditions:

1- Current smokers or smokers who have quit in the past 15 years.

2- Have at least a 30 pack year smoking history. (This is the number of years you smoked multiplied by the number of packs of cigarettes per day), and receive counseling to quit smoking if they are current smokers, and have been told by their doctor about the possible benefits, limits and have a facility where they can go that has experience in lung cancer screening and treatments.

If something abnormal is found during screening:

Sometimes screening tests will show something abnormal in the lungs or nearby areas that might be cancer. Most of these abnormal findings will turn out not to be cancer, but more CT scans or other tests will be needed to be sure.

Most often the next step is to get a repeat CT scan to see if the nodule is growing overtime. The time between scans might range anywhere from about a month to a year, depending on how likely your doctor thinks it is that the nodule could be cancer. This is based on the size, shape, and location of the nodule, as well as whether it appears to be solid or filled with fluid. If the nodule is larger, your doctor might also want to get another type of imaging test called a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which can often help tell if it is cancer.

If second scan shows that the nodule has grown, or if the nodule has other concerning features, your doctor will want to get a sample of it to check it for cancer cells. This is called a biopsy. This can be done in different ways:

1- The doctor might pass a long, thin tube called a bronchoscope down your throat and into the airways of your lung to reach the nodule. A small, hollow needle on the end of the bronchoscope can be used to get a sample of the nodule.

Fluorescence Bronchoscopy: This technique might help doctors find some lung cancer earlier, when they are likely to be easier to treat. For this test, the doctor inserts a bronchoscope through the mouth or nose and into the lung. The end of the bronchoscope has a special fluorescent light on it, instead of a normal (white) light, the fluorescent light caused abnormal areas in the airways to show up in a different color than healthy parts of the airway. Some of these areas might not be visible under white light, so the color difference can help doctors find these areas sooner, Some cancer centers use this technique to look for early lung cancers, especially if there are no obvious tumors seen with normal bronchoscopy.

Virtual bronchoscopy: This imaging test uses a chest CT scan to create a detailed 3-dimensional picture of the airways in the lung. The images can be viewed as if the doctor were actually using a bronchoscope. Virtual bronchoscopy has some possible advantages over standard bronchoscopy. First, it is non-invasive and doesn’t require anesthesia. It is also helps doctors view some airways that they might not able to get to with standard bronchoscopy, such as those being blocked by a tumor, but this test has some drawbacks as well, for example, it doesn’t show color changes in the airways that might indicate a problem. It also doesn’t let a doctor take samples of suspicious areas like bronchoscopy does, still it can be useful tool in some situations , such as in people who might be too sick to get a standard bronchoscopy.

Electromagnetic Navigation Bronchoscopy: Lung Tumors near the center of the chest can be biopsied during bronchoscopy, but bronchoscope have trouble reaching the outer parts of the lungs, so tumor in these areas often needed to be biopsied using a needle passed through the skin. First CT scans are used to create a virtual bronchoscopy. The abnormal areas is identified, and a computer helps guide bronchoscope to the area so that it can be biopsied. The bronchoscope has some special attachments that allow it to reach further than a regular bronchoscope.

2- If there is a higher chance that the nodule is cancer (or if the nodule can’t be biopsied with a needle), surgery might be done to remove the nodule and some surrounding lung tissue.

Type of lung cancer:

There are different types of lung cancer. Knowing which type is important because it affects treatment options and outlook (prognosis).

1- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): 80-85% of lung cancers

Subtypes of NSCLC; which starts from different types of lung cells, But they are grouped together as NSCLC because they approach to treatment and prognosis (outlook) are often similar.

Adenocarcinoma: About 40% of lung cancers are adenocarcinoma. These cancers start in early versions of the cells that would normally secrete substances such as mucus. This type of lung cancer occurs mainly in current or formers smokers, but it is also the most common type of lung cancer seen in non-smokers. It is more common in women than in men, and it is more likely to occur in younger people than other types of lung cancer. Adenocarcinoma is usually found in outer parts of the lung. Though it tends to grow slower than other types of lung cancer and is more likely to be found before it has spread, this varies from patient to patient. People with a type of adenocarcinoma called adenocarcinoma in situ (previously called bronchioloalveolar carcinoma) tend to have a better outlook than those with other types of lung cancer.

Squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinoma: About 25% to 30% of all lung cancers. These cancers start in early versions of squamous cells, which are flat cells that line the inside of the airways in the lungs. They are often linked to a history of smoking and tend to be found in the central part of the lungs. They are often linked to a history of smoking and tend to be fund in the central part of the lungs, near a main airway (bronchus)

Large cell (undifferentiated) Carcinoma: This type account for about 10% to 15% of lung cancers. It can appear in any part of the lung. It tends to grow and spread quickly, which can make it harder to treat. A subtype of large cell carcinoma, known as large cells neuroendocrine carcinoma, is a fast growing cancer that is very similar to small cell lung cancer.

Other Subtypes: A few other subtypes of NSCLC, such as adenosquamous carcinoma and sarcomatoid carcinoma, are much less common.

How is the stage determined?

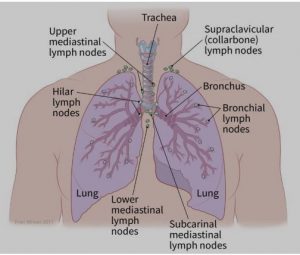

Pathology Report: The staging system most often used for NSCLC is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The size and extent of the main tumor (T): How large is the tumor? Has it grown into nearby structures or organs?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes? (See image.)

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant organs such as the brain, bones, adrenal glands, kidneys, liver, or the other lung?

Who treats lung cancer?

You may have different types of doctors on treatment team, depending on the stage of cancer and treatment options. These doctors could include:

- A thoracic surgeon: a doctor who treats diseases of the lungs and chest with surgery

- A radiation oncologist: a doctor who treats cancer with radiation therapy

- A medical oncologist: a doctor who treats cancer with medicines such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy

- A pulmonologist: a doctor who specializes in medical treatment of diseases of the lungs

How is non-small cell lung cancer treated?

A- Surgery for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Surgery to remove the cancer (often along with other treatments) may be an option for early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). If surgery can be done, it provides the best chance to cure NSCLC. Lung cancer surgery is a complex operation that can have serious consequences, so it should be done by a surgeon who has a lot of experience operating on lung cancers.

If your doctor thinks the lung cancer can be treated with surgery, pulmonary function tests will be done beforehand to see if you would still have enough healthy lung tissue left after surgery. Other tests will check the function of your heart and other organs to be sure you’re healthy enough for surgery.

Because surgery doesn’t help more advanced stage lung cancers, doctor will also want to check if the cancer has already spread to the lymph nodes between the lungs. This is often done just before surgery with mediastinoscopy.

Types of lung surgery

Different operations can be used to treat (and possibly cure) NSCLC:

- Pneumonectomy: This surgery removes an entire lung. This might be needed if the tumor is close to the center of the chest.

- Lobectomy: The lungs are made up of 5 lobes (3 on the right and 2 on the left). In this surgery, the entire lobe containing the tumor(s) is removed. This is often the preferred type of operation for NSCLC if it can be done.

- Segmentectomy or wedge resection: In these surgeries, only part of a lobe is removed. This approach might be used, for example, if a person doesn’t have enough lung function to withstand removing the whole lobe.

- Sleeve resection: This operation may be used to treat some cancers in large airways.

- The type of operation depends on the size and location of the tumor and on how well lungs are functioning. Doctors often prefer to do a more extensive operation (for example, a lobectomy instead of a segmentectomy) if a person’s lungs are healthy enough, as it may provide a better chance to cure the cancer.

When you wake up from surgery, you will have a tube (or tubes) coming out of your chest and attached to a special canister to allow excess fluid and air to drain out. The tube(s) will be removed once the fluid drainage and air leak subside. Generally, you will need to spend 5 to 7 days in the hospital after the surgery.

Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS): Increasingly, doctors now treat early-stage lung cancers in the outer parts of the lung with a procedure called video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), which requires smaller incisions than a thoracotomy.

During this operation, a thin, rigid tube with a tiny video camera on the end is placed through a small cut in the side of the chest to help the surgeon see inside the chest on a TV monitor. One or two other small cuts are created in the skin, and long instruments are passed through these cuts to do the same operation that would be done using an open approach (thoracotomy). One of the incisions is enlarged if a lobectomy or pneumonectomy is done to allow the specimen to be removed. Because only small incisions are needed, there is usually less pain after the surgery and a shorter hospital stay – typically 4 to 5 days.

Most experts recommend that only early-stage tumors near the outside of the lung be treated this way. The cure rate after this surgery seems to be the same as with surgery done with a larger incision. But it’s important that the surgeon doing this procedure is experienced, because it requires a great deal of technical skill.

B- Ablation (RFA) for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: This treatment might be an option for some people with small lung tumors that are near the outer edge of the lungs, especially if they can’t tolerate surgery.

RFA uses high-energy radio waves to heat the tumor. A thin, needle-like probe is put through the skin and moved in until the tip is in the tumor. Placement of the probe is guided by CT scans. Once the tip is in place, an electric current is passed through the probe, which heats the tumor and destroys the cancer cells.

RFA is usually done as an outpatient procedure, using local anesthesia where the probe is inserted. You may be given medicine to help you relax as well. Major complications are uncommon, but they can include the partial collapse of a lung (which often goes away on its own) or bleeding into the lung.

C- Radiation Therapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays (such as x-rays) or particles to kill cancer cells.

When might radiation therapy be used?

Depending on the stage of the non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and other factors, radiation therapy might be used:

- As the main treatment (sometimes along with chemotherapy), especially if the lung tumor can’t be removed because of its size or location, if a person isn’t healthy enough for surgery, or if a person doesn’t want surgery.

- After surgery (alone or along with chemotherapy) to try to kill any small areas of cancer that surgery might have missed.

- Before surgery (usually along with chemotherapy) to try to shrink a lung tumor to make it easier to operate on.

- To treat a single area of cancer spread, such as a tumor in the brain or an adrenal gland. (This might be done along with surgery to treat the main lung tumor.)

- To relieve (palliate) symptoms of advanced NSCLC such as pain, bleeding, trouble swallowing, cough, or problems caused by spread to other organs such as the brain. For example, brachytherapy is most often used to help relieve blockage of large airways by cancer.

D- Chemotherapy: When might chemotherapy be used?

Depending on the stage of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and other factors, chemo may be used in different situations:

- Before surgery (sometimes along with radiation therapy) to try to shrink a tumor. This is known as neoadjuvant therapy.

- After surgery (sometimes along with radiation therapy) to try to kill any cancer cells that might have been left behind. This is known as adjuvant therapy.

- Along with radiation therapy (concurrent therapy) for some cancers that can’t be removed by surgery because the cancer has grown into nearby important structures

- As the main treatment (sometimes along with radiation therapy) for more advanced cancers or for some people who aren’t healthy enough for surgery.

Chemo is often not recommended for patients in poor health, but advanced age by itself is not a barrier to getting chemo.

E- Targeted Therapy Drugs for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

As researchers have learned more about the changes in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells that help them grow, they have developed newer drugs to specifically target these changes. Targeted drugs work differently from standard chemotherapy (chemo) drugs. They sometimes work when chemo drugs don’t, and they often have different (and less severe) side effects. At this time, they are most often used for advanced lung cancers, either along with chemo or by themselves.

Drugs that target tumor blood vessel growth (angiogenesis): For tumors to grow, they need to form new blood vessels to keep them nourished. This process is called angiogenesis. Some targeted drugs, called angiogenesis inhibitors, block this new blood vessel growth:

- Bevacizumab (Avastin) is used to treat advanced NSCLC. It is a monoclonal antibody (a man-made version of a specific immune system protein) that targets vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein that helps new blood vessels to form. This drug is often used with chemo for a time. Then if the cancer responds, the chemo may be stopped and the bevacizumab given by itself until the cancer starts growing again.

- Ramucirumab (Cyramza) can also be used to treat advanced NSCLC. VEGF has to bind to cell proteins called receptors to act. This drug is a monoclonal antibody that targets a VEGF receptor. This helps stop the formation of new blood vessels. This drug is most often given after another treatment stops working. It is often combined with chemo.

Drugs that target cells with EGFR changes: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a protein on the surface of cells. It normally helps the cells grow and divide. Some NSCLC cells have too much EGFR, which makes them grow faster. Drugs called EGFR inhibitors can block the signal from EGFR that tells the cells to grow. Some of these drugs can be used to treat NSCLC.

EGFR inhibitors that also target cells with the T790M mutation: EGFR inhibitors can often shrink tumors for several months or more. But eventually these drugs stop working for most people, usually because the cancer cells develop another mutation in the EGFR gene. One such mutation is known as T790M. Osimertinib (Tagrisso) is an EGFR inhibitor that works against cells with the T790M mutation.

Doctors now commonly get another tumor biopsy when EGFR inhibitors have stopped working to see if the patient has developed the T790M mutation.

EGFR inhibitors used for squamous cell NSCLC

Necitumumab (Portrazza) is a monoclonal antibody (a man-made version of an immune system protein) that targets EGFR. It can be used along with chemotherapy as the first treatment in people with advanced squamous cell NSCLC. This drug is given as an infusion into a vein (IV).

These drugs can also cause more serious, but less common, side effects. For example, necitumumab can lower the levels of certain minerals in the blood, which can affect the heart rhythm and in some cases might be life-threatening.

Drugs that target cells with ALK gene changes: About 5% of NSCLCs have a rearrangement in a gene called ALK. This change is most often seen in non-smokers (or light smokers) who have the adenocarcinoma subtype of NSCLC. The ALK gene rearrangement produces an abnormal ALK protein that causes the cells to grow and spread. Drugs that target the abnormal ALK protein included.

These drugs can often shrink tumors in people whose lung cancers have the ALK gene change. Although they can help after chemo has stopped working, they are often used instead of chemo in people whose cancers have the ALK gene rearrangement.

Drugs that target cells with BRAF gene changes: In some NSCLCs, the cells have changes in the BRAF gene. Cells with these changes make an altered BRAF protein that helps them grow. Some drugs target this and related proteins:

- Dabrafenib (Tafinlar) is a type of drug known as a BRAF inhibitor, which attacks the BRAF protein directly.

- Trametinib (Mekinist) is known as a MEK inhibitor, because it attacks the related MEK proteins.

These drugs can be used together to treat metastatic NSCLC if it has a certain type of BRAF gene change.

F– Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Immunotherapy is the use of medicines to stimulate a person’s own immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells more effectively. Immunotherapy can be used to treat some forms of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors: An important part of the immune system is its ability to keep itself from attacking normal cells in the body. To do this, it uses “checkpoints” – molecules on immune cells that need to be turned on (or off) to start an immune response. Cancer cells sometimes use these checkpoints to avoid being attacked by the immune system. But newer drugs that target these checkpoints hold a lot of promise as cancer treatments.

- Nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) target PD-1, a protein on immune system cells called T cells that normally helps keep these cells from attacking other cells in the body. By blocking PD-1, these drugs boost the immune response against cancer cells. This can shrink some tumors or slow their growth.

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) targets PD-L1, a protein related to PD-1 that is found on some tumor cells and immune cells. Blocking this protein can also help boost the immune response against cancer cells.

Nivolumab, pembrolizumab and atezolizumab can be used in people with certain types of NSCLC whose cancer starts growing again after chemotherapy or other drug treatments. Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab can also be used as part of the first treatment in some people.

- Durvalumab (Imfinzi) also targets the PD-L1 protein. This drug is used a little differently than the other immunotherapy drugs. It is used in people with certain types of NSCLC whose cancer has not gotten worse after they have already received chemotherapy along with radiation (chemoradiation). The goal of treatment with this drug is to keep the cancer from getting worse for as long as possible.

These immunotherapy drugs are given as an intravenous (IV) infusion every 2 or 3 weeks.

2- Small Lung Cancer (SCLC): 10-15% of lung cancers

SCLC is a special type of lung cancer that tends to grow and spread quickly. Since it has often spread outside the lung at the time it is diagnosed, it is rarely treated with surgery, it is most often treated with chemotherapy, which might be combined with radiation. The chemotherapy used is different from what is used for other types of lung cancers.

Chemotherapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer: Chemotherapy (chemo) is treatment with anti-cancer drugs injected into a vein or taken by mouth. These drugs enter the bloodstream and go throughout the body, making this treatment useful for cancer anywhere in the body.

When might chemotherapy be used?

Chemo is typically part of the treatment for small cell lung cancer (SCLC). This is because SCLC has usually already spread by the time it is found (even if the spread can’t be seen on imaging tests), so other treatments such as surgery or radiation therapy would not reach all areas of cancer.

- For people with limited stage SCLC, chemo is often given along with radiation therapy. This is known as chemoradiation.

- For people with extensive stage SCLC, chemo alone is usually the main treatment (although sometimes radiation therapy is given as well).

Some patients in poor health might not be able to tolerate intense doses of chemo. But older age by itself is not a reason to not get chemo.

Drugs used to treat SCLC: SCLC is generally treated with combinations of chemotherapy drugs. The combinations most often used are:

- Cisplatin and etoposide

- Carboplatin and etoposide

- Cisplatin and irinotecan

- Carboplatin and irinotecan

Doctors give chemo in cycles, with a period of treatment (usually 1 to 3 days) followed by a rest period to allow your body time to recover. Each cycle generally lasts about 3 to 4 weeks, and initial treatment is typically 4 to 6 cycles.

Immunotherapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer:

Immunotherapy can be used to treat some people with small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors: An important part of the immune system is its ability to keep itself from attacking normal cells in the body. To do this, it uses “checkpoints”, which are proteins on immune cells that need to be turned on (or off) to start an immune response. Cancer cells sometimes use these checkpoints to avoid being attacked by the immune system. But drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors target these proteins, helping to restore the immune response against cancer cells.

- Nivolumab (Opdivo) targets PD-1, a protein on T cells (a type of immune system cell) that normally helps keep these cells from attacking other cells in the body. By blocking PD-1, this drug boosts the immune response against cancer cells. It is used to treat advanced SCLC in people whose cancer continues to grow after getting at least two previous lines of treatment, including chemotherapywith either cisplatin or carboplatin.

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) targets PD-L1, a protein related to PD-1 that is found on some tumor cells and immune cells. Blocking this protein can also help boost the immune response against cancer cells. This drug can be used as part of the first-line treatment for advanced SCLC, along with the chemo drugs carboplatin and etoposide.

These drugs are given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, typically every 2 or 3 weeks.

Radiation Therapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer: Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays (such as x-rays) or particles to kill cancer cells.

When is radiation therapy used? Depending on the stage of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and other factors, radiation therapy might be used in several situations:

- In limited stage SCLC, radiation therapy can be given at the same time as chemotherapy (chemo) to treat the tumor and lymph nodes in the chest. Giving chemo and radiation together is called concurrent chemoradiation. The radiation may be started with the first or second cycle of chemo.

- Radiation can also be given after the chemo is finished. This is sometimes done for patients with extensive stage disease, or it can be used for people with limited stage disease who have trouble getting chemotherapy and radiation at the same time (as an alternative to chemoradiation).

- SCLC often spreads to the brain. Radiation can be given to the brain to help lower the chances of problems from cancer spread there. This is called prophylactic cranial irradiation. This is most often used to treat people with limited stage SCLC, but it can also help some people with extensive stage SCLC.

- Radiation can be used to shrink tumors to relieve (palliate) symptoms of lung cancer such as pain, bleeding, trouble swallowing, cough, shortness of breath, and problems caused by spread to other organs such as the brain.

Types of radiation therapy: The type of radiation therapy most often used to treat SCLC is called external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). It delivers radiation from outside the body and focuses it on the cancer.

Treatment is much like getting an x-ray, but the radiation is more intense. The procedure itself is painless. Each treatment lasts only a few minutes, although the setup time – getting you into place for treatment – usually takes longer.

Most often, radiation as part of the initial treatment for SCLC is given once or twice daily, 5 days a week, for 3 to 7 weeks. Radiation to relieve symptoms and prophylactic cranial radiation are given for shorter periods of time, typically less than 3 weeks.

In recent years, newer EBRT techniques have been shown to help doctors treat lung cancers more accurately while lowering the radiation exposure to nearby healthy tissues. These include:

Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT): 3D-CRT uses special computer programs to precisely map the location of the tumor(s). Radiation beams are shaped and aimed at the tumor(s) from several directions, which makes it less likely to damage normal tissues.

Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): IMRT is an advanced form of 3D therapy. It uses a computer-driven machine that moves around the patient as it delivers radiation. Along with shaping the beams and aiming them at the tumor from several angles, the intensity (strength) of the beams can be adjusted to limit the dose reaching nearby normal tissues. This technique is used most often if tumors are near important structures such as the spinal cord. Many major cancer centers now use IMRT.

A variation of IMRT is called volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT). It uses a machine that delivers radiation quickly as it rotates once around the body. Each treatment is given over just a few minutes.

Surgery for Small Cell Lung Cancer: Surgery is rarely used as part of the main treatment for small cell lung cancer (SCLC), as the cancer has usually already spread by the time it is found.

Because surgery isn’t helpful for more advanced stage lung cancers, your doctor will also want to make sure the cancer hasn’t already spread to the lymph nodes between the lungs. This is often done just before surgery with mediastinoscopy or with some of the other techniques. If cancer cells are in the lymph nodes, then surgery is not likely to be helpful.

3- Lung Carcinoid Tumors: Fewer than 5% of lung cancers are lung carcinoid tumors. Carcinoid tumors are special type of tumor. They start from cells of the diffuse neuroendocrine system. This system is made up of cells that are like nerve cells in certain ways and like hormone-making endocrine cells in other ways. These cells do not form an actual organ like the adrenal or thyroid glands. Instead, they are scattered throughout the body in organs like the lungs, stomach, and intestines. Like most cells in your body, the lung neuroendocrine cells sometimes go through certain changes that cause them to grow too much and forms tumors. These are known as neuroendocrine tumors or neuroendocrine cancers.

There are 4 types of neuroendocrine lung tumors:

– Typical carcinoid tumor (Well-differentiated NEC)

– Atypical carcinoid (Moderately-differentiated NEC)

– Small cell carcinoma (Poorly-differentiated NEC)

– Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (Poorly-differentiated NEC)

Typical Carcinoid Tumors: are not linked to smoking. They tend to be slow growing, and only rarely spread outside the lungs.

Atypical Carcinoid Tumors: grow a little faster and are somewhat more likely to spread to other organs. Seen under a microscope. They have more cells in the process of dividing and look more like a fast growing tumor. They are much less common than typical carcinoids. Some of the features of an atypical carcinoid that may be mentioned in pathology report include: mitotic figures or mitoses (an indication of how fast the tumor is growing), and necrosis (when areas of the tumor are dead)

Some carcinoid tumors can release hormone-like substances into the bloodstream, which might cause symptoms, Lung carcinoids do this far less often than carcinoid tumors that start in the intestines.

Surgery to Treat Lung Carcinoid Tumors: Surgery is the main treatment for lung carcinoid tumors whenever possible. If the tumor hasn’t spread, it can often be cured by surgery alone.

Types of lung surgery: Different operations can be used to treat (and possibly cure) lung carcinoid tumors. These operations require general anesthesia (where you are in a deep sleep) and are usually done through a surgical incision between the ribs in the side of the chest (called a thoracotomy).

Pneumonectomy & Lobectomy& Segmentectomy or wedge resection & and/or Sleeve resection.

Chemotherapy for Lung Carcinoid Tumors: Unfortunately, carcinoid tumors usually do not respond very well to chemo. It is mainly used for carcinoid tumors that have spread to other organs, are causing severe symptoms, have not responded to other medicines, or atypical carcinoids that are dividing quickly. Sometimes, it may be given after surgery. Because chemo does not always shrink carcinoid tumors, it is important to ask doctor about the chances of it helping and if the benefits are likely to outweigh the risk of side effects.

Other Drug Treatments for Lung Carcinoid Tumor: For people with metastatic lung carcinoid tumors, several medicines can help control symptoms and tumor growth.

Radiation Therapy for Lung Carcinoid Tumors: Radiation therapy may be an option for those who can’t have surgery for some reason. It may also be given after surgery in some cases if there’s a chance some of the tumor was not removed. Radiation therapy can also be used to help relieve symptoms such as pain if the cancer has spread to the bones or other areas.

External beam radiation therapy: uses a machine that delivers a beam of radiation to a specific part of the body. This is the type of radiation used most often for lung carcinoid tumors.

Radioactive drugs: Another type of radiation therapy uses drugs containing radioactive particles. This type of treatment is called peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) and may be useful in treating some widespread carcinoid tumors.

4- Other Lung Tumors: Including adenoid cystic carcinomas, lymphomas, and sarcomas as well as benign tumors as hamartomas and cancer that spread to the lungs which start in other organs (such as breast, pancreas, kidney, or skin) can sometimes spread (metastasize) to the lungs.

References:

American Cancer Society

Forde, M, Chaft, J, Smith, K, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blokade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378: 1976-1986

PAYING IT FORWARD

Paying it Forward

Since its beginning, SEPA Labs has given back to the community. Because the laboratory is closely tied to the local community, it’s essential also to remain an active participant. In the early years, the company made an impact by donating to the local library. Today, the company boosts community involvement when sponsoring employees participating in the annual charity bridge run and each year the employees of the laboratory give generously to the local food bank and toy drive.

A few weeks ago, Dr. Michael Mazzotta gave a presentation to the Youth Leadership of Glynn which was attended by high school students representing all of the area schools See news article here: https://thebrunswicknews.com/news/local_news/students-visit-morgue-for-lesson-on-human-anatomy/article_2a399db2-eef0-5d65-966b-9fa0f448043f.html. The presentation was approximately 75 minutes long, but is always well attended and is the highlight of the hospital tours.

Whether as an individual, a group or the company as a whole, SEPA Labs and its employees have given back to the community since the founding of the company because any action large or small can make a real difference.

Pathologist’s Corner – Dr. Cecilia Rosales on Skin Cancer

What is skin cancer?

Skin cancer is the most common of all cancers. Most skin cancers are slow-growing easy to recognize and relatively easy to treat when detected early. Most skin cancers are caused by too much exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays, mostly from the sun, but also from tanning beds.

Types of skin cancer

Non-Melanoma: are the most common types of skin cancer and include Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. The tumors can be fast or slow growing, but rarely spread. Commonly found on sun exposed parts of body. They are called non-melanomas because they develop from skin cells other than melanocytes (the cells that make the brown pigment that gives skin its color).

Melanoma: are less common, but more serious. Almost always curable when detected early, but more likely to spread to other parts of body. A melanoma begins in the melanocytes and can occur anywhere on the skin but is more common in the trunk in men and in the legs in women.

What should I know about early detection of skin cancer?

Get a cancer-related checkup by a doctor, including skin examination, every three years between ages 20 and 40 and annually for those 40 and older.

It’s important to check your own skin, preferably once per month and to see a doctor immediately if you notice any warning signs.

What should I look for?

Look for new growths, spots, bumps, patches, or sores that don’t heal after 2 to 3 months.

Basal cell carcinomas often look like flat, firm, pale areas or small, raised, pink or red, translucent, shiny, waxy areas that may bleed after a minor injury. They may have one or more abnormal blood vessels, a lower area in their center, and/or blue, brown, or black areas. Large basal cell carcinomas may have oozing or crusted areas.

Squamous cell carcinomas may look like growing lumps, often with a rough, scaly, or crusted surface. They may also look like flat reddish patches in the skin that grow slowly.

Both of these types of skin cancer may develop as a flat area showing only slight changes from normal skin.

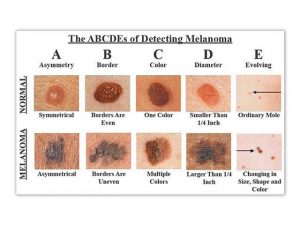

To spot Melanoma use the ABCD Rule:

The “ABCD rule” is an easy guide to the usual signs of melanoma.

A (Asymmetry) one portion of the mole does not match the other

B (Border) edges are irregular, notched, or blurred

C (Color) different shades of black or brown, patchy colors

D (Diameter) spot is 6 millimeters across, or growing large

E (Evolving) change in the size, shape, or color of a mole or the appearance of a new spot.

Some melanomas do not fit the ABCD rule described above, so it is very important to tell your doctor about any changes in skin markings or new spots on your skin. Other warning signs are a sore that does not heal, spread of pigment from the border of a spot to surrounding skin redness or a new swelling beyond the border. Also, change in sensation — itchiness, tenderness, or pain change in the surface of a mole, scaliness, oozing, bleeding, or the appearance of a bump or nodule. A mole that looks very different from your other moles is to be shown to your health care provider. Melanomas can also develop in the nails, genital area and oral cavity.

How to check your skin:

A self-exam is best done once a month in a well-lit room in front of a full-length mirror. A hand-held mirror can be used for areas that are hard to see. Check your face, ears, neck, chest, and belly. Women will need to lift breasts to check the skin underneath. Check your scalp, your mouth and your genital area. The first time you inspect your skin, spend a fair amount of time carefully going over the entire surface of your skin. Learn the pattern of moles, blemishes, freckles, and other marks on your skin so that you’ll notice any changes next time. Any trouble spots should be seen by a doctor.

How is skin cancer diagnosed?

If there is any chance that you suspect you may have skin cancer, you should see a dermatologist. He or she will look at the area closely and determine what steps to take next. The spot may be recorded via photograph or computer image. If the doctor thinks that an area of skin might be cancerous, he or she will take a sample of skin from the suspicious area to look at under a microscope. This is called a skin biopsy.

How is skin cancer treated?

Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, cryosurgery, laser surgery, skin grafting & reconstructive surgery depending of the stage and characteristic of the tumor.

Why is it important to get regular skin cancer screenings?

Most basal and squamous cell cancers can be cured if the cancer is detected and treated early. If detected in its earliest stages and treated properly, melanoma is also highly curable.

Five-year survival rate when melanoma is found at its earliest stage is about 99%

Five-year survival rate when melanoma is found after it has spread is about 18%

If you want to learn more, call 1-800-ACS-2345 or visit www.cancer.org for more information about skin cancer or any other cancer-related topic.

References: American Cancer Society

Michael Schubert Interviews Dr. Patrick Godbey

Time to Get Political by Michael Schubert – The Pathologist – www.pathologist.com

“Grassroots politics can promote and protect pathology through advocacy and education. PathNET is getting pathologists involved and giving them a voice”

Click on the link below:

Michael Schubert interviews Dr. Patrick Godbey

Pathologist’s Corner – Dr. Xuebin Yang MD, PhD on Barrett’s Esophagus

Patient’s Guide to Barrett’s Esophagus

What is Barrett’s Esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus is a precancerous condition and refers to metaplastic conversion of normal squamous epithelium of tubular esophagus (see figure a) to columnar epithelium (figure b). Normally the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) divides the esophagus and stomach and corresponds to squamocolumnar junction (SCJ “Z-lin”). The esophagus is lined by stratified squamous epithelium. The stomach is lined by columnar epithelium. In some chronic injury setting such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the esophageal squamous epithelium goes through a metaplastic process and is converted to a columnar epithelium with goblet cells (which are usually found lower in the gastrointestinal tract and thus also called “intestinal metaplasia”).

The main cause of Barrett’s esophagus is thought to be an adaptation to chronic acid exposure from GERD. GERD is associated with a 10–15% risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Other risk factors associated with the development of Barrett’s esophagus include male gender, central obesity and age over 50 years.

What is the clinical complication of Barrett’s Esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus is the only recognized precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma which incidence has been increasing in the United States since 1970s. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus have a 30-125 fold higher risk of developing cancer of the esophagus than the general population.

How is Barrett’s Esophagus diagnosed?

Diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus requires esophagogastroduodenoscopy (a procedure in which a fibreoptic cable is inserted through the mouth to examine the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum) and biopsy of esophageal lining. According to American College of Gastroenterology guideline, Barrett’s esophagus should be diagnosed when there is extension of salmoncolored mucosa into the tubular esophagus extending ≥1 cm proximal to the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) with biopsy confirmation of intestinal metaplasia.

Barrett’s esophagus, based on the histopathology, is classified into five categories: nondysplastic, indefinite for dysplasia, low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma.

Who should be screened for Barrett’s Esophagus?

Screening for Barrett’s esophagus may be considered in men with chronic (>5 years) and/or frequent (weekly or more) symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux (heartburn or acid regurgitation) and two or more risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma. These risk factors include: age >50 years, Caucasian race, presence of central obesity (waist circumference >102 cm or waist–hip ratio (WHR) >0.9), current or past history of smoking, and a confirmed family history of Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma (in a first-degree relative).

Given the substantially lower risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in females with chronic GERD symptoms (when compared with males), screening for Barrett’s esophagus in females is not recommended. However, screening could be considered in individual cases as determined by the presence of multiple risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma (age >50 years, Caucasian race, chronic and/or frequent GERD, central obesity: waist circumference >88 cm, WHR >0.8, current or past history of smoking, and a confirmed family history of Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma (in a first-degree relative).

Screening of the general population is not recommended.

If initial endoscopic evaluation is negative for Barrett’s esophagus, repeating endoscopic evaluation for the presence of Barrett’s esophagus is not recommended. If endoscopy reveals esophagitis, repeat endoscopic assessment after proton pump inhibitor therapy for 8–12 weeks is recommended to ensure healing of esophagitis and exclude the presence of underlying Barrett’s esophagus.

What is the surveillance of patients with Barrett’s Esophagus?

The goal of a screening and surveillance program for Barrett’s esophagus is to identify individuals at risk for progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma.

For Barrett’s esophagus patients without dysplasia, endoscopic surveillance should take place at intervals of 3 to 5 years.

Patients diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus on initial examination do not require a repeat endoscopy in 1 year for dysplasia surveillance.

For patients with indefinite for dysplasia, a repeat endoscopy after optimization of acid suppressive medications for 3–6 months should be performed.

If the indefinite for dysplasia reading is confirmed on this examination, a surveillance interval of 12 months is recommended.

For patients with confirmed low-grade dysplasia and without life-limiting comorbidity, endoscopic therapy is considered as the preferred treatment modality, although endoscopic surveillance every 12 months is an acceptable alternative.

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus and confirmed high-grade dysplasia should be managed with endoscopic therapy unless they have life-limiting comorbidity.

How is Barrett’s Esophagus treated?

Treatments for Barrett’s esophagus include chemoprevention, endoscopic therapy and surgical therapy.

Chemoprevention

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus should receive once-daily proton pumper inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

Aspirin or NSAIDs should not be routinely prescribed to patients with Barrett’s esophagus as an antineoplastic strategy. Similarly, other putative chemopreventive agents currently lack sufficient evidence and should not be administered routinely.

Endoscopic therapy

Patients with nodularity in the Barrett’s esophagus segment should undergo endoscopic mucosal resection of the nodular lesion(s) as the initial diagnostic and therapeutic maneuver. Histologic assessment of the endomucosal resection (EMR) specimen should guide further therapy. In subjects with EMR specimens demonstrating high grade dysplasia, or intramucosal carcinoma, endoscopic ablative therapy of the remaining Barrett’s esophagus should be performed.

In patients with EMR specimens demonstrating neoplasia at a deep margin, residual neoplasia should be assumed, and surgical, systemic, or additional endoscopic therapies should be considered.

Endoscopic ablative therapies should not be routinely applied to patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus because of their low risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Endoscopic eradication therapy is the procedure of choice for patients with confirmed low grade dysplasia, and confirmed high grade dysplasia.

In patients with T1a esophageal adenocarcinoma, endoscopic therapy is the preferred therapeutic approach, being both effective and well tolerated.

In patients with T1b esophageal adenocarcinoma, consultation with multidisciplinary surgical oncology team should occur before embarking on endoscopic therapy. In such patients, endoscopic therapy may be an alternative strategy to esophagectomy, especially in those with superficial (sm1) disease with a well-differentiated neoplasm lacking lymphovascular invasion, as well as those who are poor surgical candidates.

In patients with known T1b disease, EUS may have a role in assessing and sampling regional lymph nodes, given the increased prevalence of lymph node involvement in these patients compared with less advanced disease.

In patients with dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus who are to undergo endoscopic ablative therapy for nonnodular disease, radiofrequency ablation is currently the preferred endoscopic ablative therapy.

Surgical therapy

Antirefleux surgery should not be pursued in patients with Barrett’s esophagus as an antineoplastic measure. However, this surgery should be considered in those with incomplete control of reflux symptoms on optimized medical therapy.

In cases of Barrett’s esophagus with invasion into the submucosa, especially those with invasion to the mid or deep submucosa (T1b, sm2–3), esophagectomy, with consideration of neoadjuvant therapy, is recommended in the surgical candidate.

In patients with T1a or T1b sm1 adenocarcinoma, poor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, or incomplete endoscopic mucosal resection should prompt consideration of surgical and/or multimodality therapies.

HAPPY Pathologists’ Assistant Day

We at Southeastern Pathology Associates would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge our Pathology Assistants for their dedication and hard work.

A pathologists’ assistant (PA) is a highly trained allied health professional who provides various services under the direction and supervision of a pathologist. Southeastern Pathology Associates PAs are academically and practically trained to provide accurate and timely processing of laboratory specimens.

For more information on Pathologists’ Assistant Day please click here